⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 6 min read

T4L: Hello, Dr. Rogers, and welcome to Theology for Life Magazine. Can you tell us a bit about yourself, including the current ministries you are involved in?

Ben Rogers: I am the husband of Christie, the father of Henry and Hugh, the pastor of a small church, and the Bible and Latin teacher at Christ Covenant School in Ridgeland, Mississippi.

I published a biography of J. C. Ryle with Reformation Heritage Books entitled, A Tender Lion: The Life, Ministry, and Message of J. C. Ryle. And I have just edited and introduced a new edition of Ryle’s Simplicity in Preaching: A Few Hints on a Great Subject with H&E Publishing.

T4L: Who is J.C. Ryle?

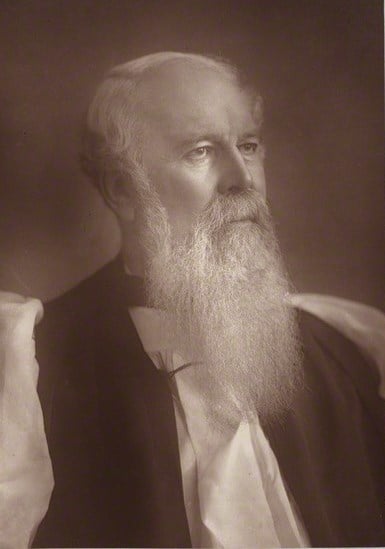

Ben Rogers: The short and simple answer goes something like this: J. C. Ryle was the son of a wealthy Cheshire family, whose father’s bankruptcy propelled him into the ministry of the Church of England, where he distinguished himself as a preacher, pastor, author, reformer, controversialist, party leader, and bishop.

Ryle was a committed Evangelical churchman, with a deep and abiding love for the English Reformers, Puritans, and leaders of the Evangelical Revival of the 18th Century, as his historical and biographical writings bear witness. But above all, Ryle loved the Scriptures—“Here is rock: all else is sand.” And he devoted his life to teaching, preaching, and applying the Scriptures to his parishes, diocese, and to his readers more broadly.

T4L: And, why does J.C. Ryle’s work continue to be so influential?

Ben Rogers: I think the answer is twofold. Ryle’s writings tend to focus almost exclusively on the essentials of the Gospels. For example, in volume 1 of Expository Thoughts on the Gospels, Ryle explains the focus of his exposition:

I have constantly left unsaid many things that might have been said, and have endeavored to dwell chiefly on the things needful to salvation. I have deliberately passed over many subjects of secondary importance, in order to say something that might strike and stick in consciences.

The same focus can be found in his other writings. He rarely discusses issues that divide evangelical Protestants, and when he does he is remarkably charitable. Ryle’s gospel-focus combined with his catholic spirit probably explain why his works have had a pan-denominational appeal.

Ryle’s distinct writing style has also contributed to his staying power. Victorian preachers tended to be verbose in the extreme, as the pulpit increasingly came under the influence of the novel.

Since then, literary tastes have changed, and the long, flowing, wordy, clause-filled, prose of the Victorians has gone out of fashion, as have the works of Victorian clergymen who wrote in that style. J. C. Ryle, however, never embraced the literary conventions of his day.

Preaching to rural congregations made up almost entirely of agricultural laborers taught him “crucify” his style and aim for simplicity and directness in preaching as well as writing. Ryle’s distinctive style makes his work accessible to modern readers, who may otherwise struggle with the unabridged, Latinized English of a John Owen or William Romaine. Readers may not always agree with what he says, but they know what he is saying and they feel as though they are being addressed personally.

T4L: Do you think we again need men like J.C. Ryle? What would that look like in terms of their character and ministry?

Ben Rogers: I definitely think we need more men like Ryle in ministry. If the Lord raised up more men, they would be men who love their Bibles and their Savior. They would be convictionally and confessionally Reformed and Protestant, with a deep and abiding love for Puritan theology and spirituality. They would pray for revival, but be devoted to the ordinary means of grace, especially preaching, worship, prayer, and Bible study.

Preaching would be their top ministerial priority, and they would labor to make their sermons simple, direct, and full of Christ. They would be diligent pastors, who would make it a point to be in the homes of their flock. They would be concerned about the health of their denominational body as well as their own church. They would labor to make them more scripturally sound and pastorally effective. They would promote evangelism at home and missions abroad. And last but not least, they would be men who pursue holiness.

T4L: I would agree; his pursuit of holiness is something we should all strive to imitate. How did J.C. Ryle deal with controversy, and how can his example instruct Christians to handle controversy today?

Ben Rogers: J. C. Ryle participated in nearly every controversy involving evangelical churchmen from around 1860 forward. He considered the emergence of ritualism and neologianism [adopting novel views] to be the two most serious threats to Protestant and evangelical orthodoxy, but he was involved in a number of other theological skirmishes as well. Holiness, it should be remembered, was written in response to one of these lesser controversies—the emergence of the Keswick Movement.

In The Tender Lion, I tried to show that Ryle was driven by two related pastoral concerns. He wanted to do “good to souls”, which he defined as “conversion for the unconverted, decision for the wavering, and growth in grace for the believer”, and to make the Church of England more pastorally effective. When false teaching or unbiblical practices threatened to undermine these pursuits, Ryle felt compelled by his ordination vows to “drive away all strange and erroneous doctrines which are contrary to God’s word”.

I think Ryle’s discrimination as a controversialist is certainly worthy of imitation. With the advent of the internet and social media, it is easier than ever to pick a theological fight. Ryle’s example helps us discern when controversy becomes a positive necessity and when it is not.

Ryle’s integrity as a controversialist is also praiseworthy. His controversial writings always focused on ideas, not people, and he never engaged in personal attacks. In fact, I can’t think of a single instance when he spoke ill of an opponent. When he named them, which he almost never did, it was typically to compliment them. His opponents weren’t so kind. Charles Spurgeon criticized Ryle by name in The Sword and the Trowel on more than one occasion, and some of his ritualistic opponents stooped so low as to mock his marriages (Ryle married and buried three wives during his lifetime) in print.

T4L: It’s a sad thing to see Church leadership mock fellow leaders/believers in this way. Unfortunately, that type of response to controversy has only increased in our day and age. We should definitely be looking toward Ryle as an example, as you’ve mentioned. Thank you for taking time out of your busy schedule to do this interview, Dr. Rogers.

Bennett Wade Rogers (PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is a pastor and teacher in Mississippi. He is the author of A Tender Lion: The Life, Ministry, and Message of J. C. Ryle (2019) and has recently edited and introduced a new edition of Ryle’s Simplicity in Preaching: A Few Hints on a Great Subject (2019).