⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 5 min read

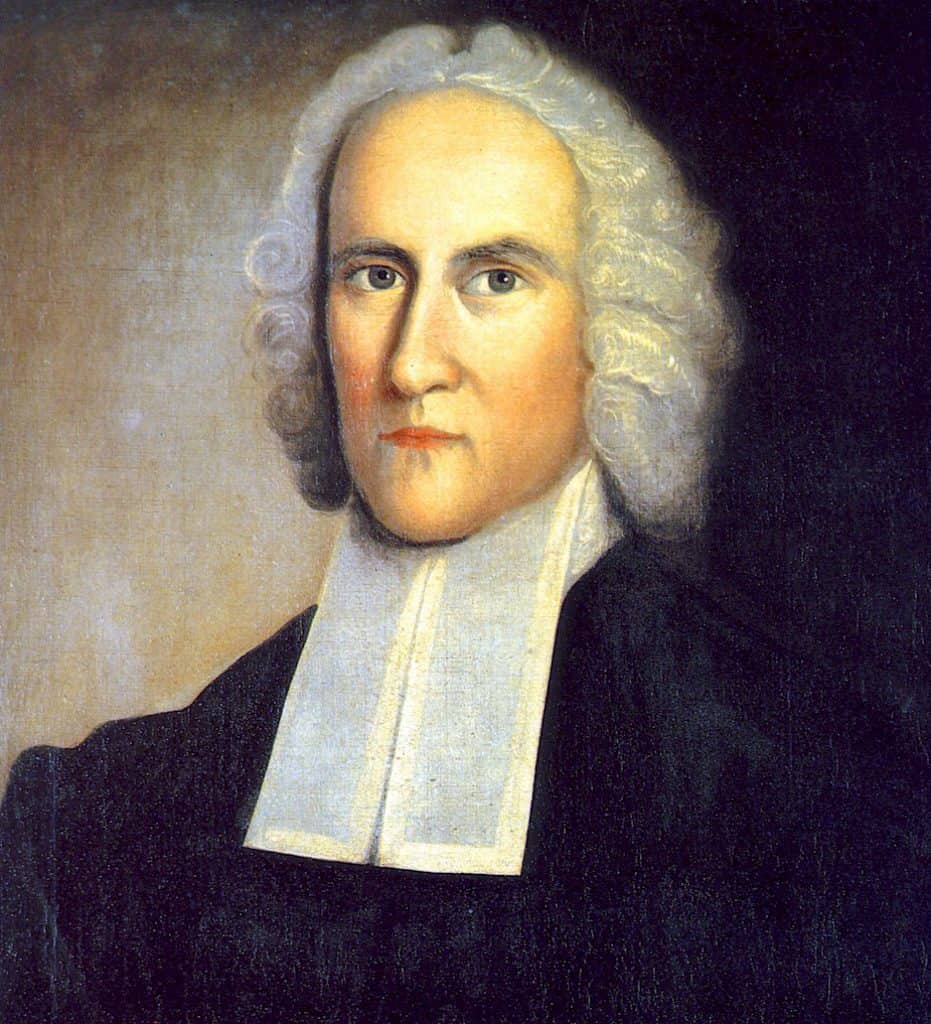

In order to gather a sense of Jonathan Edwards’ titanic legacy in American religious history, one needs only to survey the host of nicknames ascribed to him by various scholars through the years. In 1988, Robert Jenson pronounced Edwards “America’s theologian”. For the seemingly endless shadow he still casts upon American Protestantism, Richard Niebuhr boldly declared Edwards to be “the American Augustine” (1937). In an early eighteenth century, New England, dominated intellectually by English and Continental authors, it was a Congregationalist preacher’s son from rural East Windsor, Connecticut who would become America’s first dominant, trans-Atlantic theologian. However, he was also, in a very real sense, America’s first original thinker.

According to Edwards’ disciple Samuel Hopkins, Edwards “called no man father” (1765). Unafraid to pour modern wine into the old wineskins of Puritanism, Edwards renovated traditional Reformed doctrines, like original sin and the rebirth with newer metaphysical, philosophical, and psychological concepts. He was, in the words of Perry Miller, “the apotheosis of Puritanism” (1949).

Still, Edwards was more than a mind; he was also a pastor seeking to shepherd his Northampton congregation, as well as an entire generation. Therefore, perhaps more fitting is Sydney Ahlstrom’s characterization of Edwards as “America’s and possibly the Church’s greatest apostle to the Enlightenment” (1961).

For instance, Edwards co-opted John Locke’s empiricism in order to redefine faith in terms of an “idea” in Christ. He adopted Locke’s belief that “actions are to be ascribed to agents, and not properly to the powers of agents” in order to refute the Arminian notion of the self-determining will (1754). In an era that celebrated the autonomy and glory of humanity, it was Edwards who held the sovereignty of God and the freedom of depraved man in tension—a precarious balance that would later aid Edwardseans—William Carey, Andrew Fuller—and an entire missions movement built upon the dual notions of God’s providence and man’s natural ability.

If Jonathan Edwards cannot be properly contextualized without the Enlightenment, he cannot be adequately appreciated without the Great Awakening. Beginning in the winter of 1733 and extending to 1735, a “season of harvest” broke out in Edwards’ Northampton parish. By 1739, Edwards’ first masterpiece, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God (1736), went through three editions and twenty printings across the Atlantic.

The astonishing account served as inspiration for the Great Awakening of the 1740s, as well as for revivals in Scotland and England. In the aftermath of the Awakening’s enthusiasm and hysteria, many anti-revivalists sought to discredit the entire movement, but Edwards rightly defended the revival as a work of God. His manuscript, Distinguishing Marks of the Work of the Spirit of God (1741), delivered at the height of the revival, is a newer, more flexible take on the traditional Puritan notion of the ordo salutis, as well as his imprimatur for the spiritual legitimacy of the Awakening. However, the extreme aberrations and arrogant delusions of the revival were also discrediting the work of Christ. Therefore, Edwards responded to both sides, the rationalists and the enthusiasts. His Religious Affections (1746), penned after the Awakening and constructed from the salient themes of his sermon “Divine and Supernatural Light” (1734), is a via media of sorts and a virtual summary of Edwards’ conversion psychology. “True religion,” Edwards insisted, “in great part, consists in holy affections.”

At every turn, Edwards was willing to package Scriptural truths in Enlightenment thought in order to defend the authenticity of the Awakening and to demonstrate the “nature of true religion”. For a nation in social, political, philosophical, and theological flux, Edwards was, as George Marsden has identified him, “both” a medieval and a modern (2003). For such a time in America, God delivered a mind and a soul as bold as an Edwards.

As a modern Reformed thinker, and as a pastor who was willing to risk (and ultimately lose) his pulpit for the sake of aligning his doctrine of salvation with his doctrine of the church, Edwards continues to speak practically to pastors and lay Christians alike. John Piper, for example, has boasted that his notion of “Christian Hedonism” is, in so many ways, simply a “recovery” of Edwards’ teachings on God’s sovereignty and the joy found in Christ (1986).

Unfortunately, while so much of Edwards lives on in evangelicalism today, most Americans know their “Augustine” simply for the imprecatory sermon he delivered at Enfield in 1741, entitled, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. Too few Christians have ever read his first published work, God Glorified in Man’s Dependence (1731), delivered when he was just 28 years old, or his work entitled, The Nature of True Virtue (1765), which, according to Edwards, “most essentially consists in a supreme love to God.”

Too few have ever read Heaven is a World of Love (1738), wherein Edwards describes the “garden of pleasures” and the “perfect enjoyment” of the saints in the love of Jesus. It was Edwards who believed, like Augustine, that the Holy Spirit was love. And therefore, he was incapable of speaking about the Triune God without mentioning this monumental theme. Above all else, Edwards’ central theme was love. Perhaps, instead of remembering him as a sullen, angry, monotone Puritan, without remorse or affection for his people, we would best remember Edwards by the nickname given by Joseph Haroutunian: “the theologian of the Great Commandment” (1944). By the grace of God, Edwards was a prolific writer who spent nearly 13 hours in his study each day. His writings are here for us to read. Today, Edwards continues to speak to the church, not simply a theologian, but as a pastor and sinner.