⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 4 min read

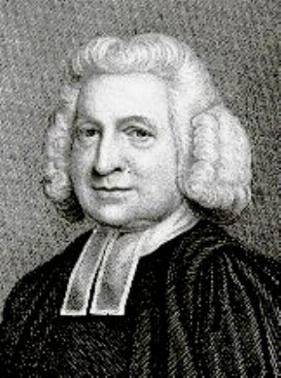

George Whitefield was the most famous man in America before the American Revolution. The Church of England minister was the most visible leader of the Great Awakening, a series of revivals that swept through Britain and America in the mid-eighteenth century, invigorating the faith of untold thousands. Whitefield drew massive audiences wherever he went, and his publications alone doubled the output of the American colonial presses between 1739 and 1742. If there is any Christian historical figure with which to compare Whitefield, it would be Billy Graham in the twentieth century. But Graham was following a path that Whitefield cut first.

What made Whitefield and his gospel message so famous? First, Whitefield mastered the use of the new media of his time. Cultivating a vast network of newspaper publicity, printers, and letter-writing correspondents, Whitefield used all means available to get the word out about the gospel. He employed the best new media experts of the time, whether they agreed with his gospel message or not. Most importantly, he partnered with Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, who became Whitefield’s key printer in America, even though Franklin was no evangelical. Their business relationship transformed into a close friendship, although Whitefield routinely pressed Franklin about his need for Jesus. “As you have made a pretty considerable progress in the mysteries of electricity,” Whitefield wrote to Franklin in 1752, “I would now humbly recommend to your diligent unprejudiced pursuit and study the mystery of the new-birth.” Franklin never accepted Whitefield’s evangelistic overtures, but Franklin always insisted that Whitefield was a man of impeccable integrity.

Whitefield also wielded incredible God-given talent for preaching. I wish we had a YouTube clip of Whitefield’s preaching, but we can imagine what it was like to hear him based on the testimonies of contemporaries. David Garrick, one of England’s most famous actors of the time, noted with a touch of jealousy that Whitefield could “make men weep or tremble by his varied utterances of the word ‘Mesopotamia.’” Whitefield trained as an actor himself as a young man, and he adapted theater techniques to his preaching. Taking on the character of biblical figures during his sermons (which were often delivered outdoors to accommodate the vast crowds), he would weave dramatic, emotional stories rather than reciting dry doctrine from a written text. Whitefield was also able to project his resonant voice far across the wide fields. Franklin estimated that as many as thirty thousand people could hear Whitefield speaking at one time—without electric amplification, of course.

Whitefield’s talent for media and public performance raises the question of his sincerity. Was he just an evangelical salesman, more concerned with his own fame and profit than really bringing people to God? Whitefield confessed his struggles with the “fiery trial of popularity” that came along with his celebrity status, including the temptations of arrogance and self-indulgence. But Whitefield seems to have weathered that trial as well as any famous pastor. He did not personally profit much from his ministry. Most of his donation revenues went into his charitable projects (especially an orphanage in Georgia), and into the costs of traveling all over Britain and America. Whitefield’s greatest personal failing was one shared by many prominent whites in America: he was a slave owner. He did criticize masters’ abuse of slaves in the South and believed that Christian masters should evangelize and educate enslaved people. But this idea of “benevolent” enslavement strikes modern observers as an insufferable contradiction. Whitefield, along with other slave-owning Founders (including Ben Franklin), compounded the glaring incongruity of holding people in bondage while trumpeting the value of liberty.

In spite of his obvious failings, Whitefield was a gospel minister of great seriousness. The Bible, he proclaimed, showed that people’s sins separated them from God, but that Jesus offered them forgiveness and freedom through his death on the cross, and his resurrection from the dead. That message drove Whitefield to risk health and safety in his relentless schedule. Although it is impossible to count precisely, he probably delivered around 18,000 sermons during his ministry, routinely preaching twice or more a day. He survived multiple assassination attempts by people who hated him, or who wanted to become famous themselves. Not only did he traverse the length of the American colonies from Maine to Georgia, but he made an incredible thirteen transatlantic voyages between Britain and America, any one of which could easily have led to his death. His strength finally ran out on his last visit to America, where he died (and is buried) in Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1770.

Thomas S. Kidd teaches history at Baylor University, and is Associate Director of Baylor’s Institute for Studies of Religion. Dr. Kidd writes at the Evangelical History blog at The Gospel Coalition. He also regularly contributes for outlets such as WORLD Magazine, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. His recent books include Benjamin Franklin: The Religious Life of a Founding Father; George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father; and Baptists in America: A History, with co-author Barry Hankins.