⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 6 min read

“Father, thy word is past, man shall find grace” — John Milton, Paradise Lost

I feel the seasons in my bones. They come. They go. Each passing season deposits its residue—memories, laughter, disappointments—fashioning layers like leaves. Those are the seasons of aging. There is no avoiding the seasons. There is no ignoring them. Artifacts—souvenirs—appear to mark the departure from one season-spent and the entrance to the next. We bear the artifacts on our very bodies. Mostly, we carry them in our emotional rucksacks. But what if the deepening impressions of human development—or devolution—were really divine motifs that shape the human soul?

Eric Erikson famously developed a theory of eight human life stages. Each phase is navigated with both a struggle to accept the next season and resistance to move forward. Conflict can crush the possibility of actually savoring the season we are in. Nothing is more tragic than losing time.

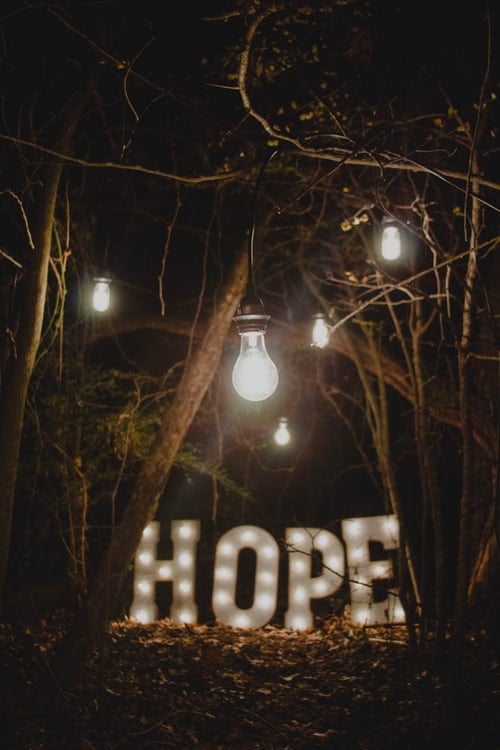

Conflict persists. Inner spiritual conflict, manifesting itself in a variety of tale-tell signs—some of those even troubling—is probably the most persistent dynamic in the lifelong journey of seasonal travel. Erikson observed that there is another positively-charged atomic particle floating in the protoplasm of human existence. It is hope.

“Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive. If life is to be sustained hope must remain, even where confidence is wounded, trust impaired.”—Erik Erikson, The Erik Erikson Reader, 2000

Hope is the currency of the Christian life. Our hope—for I know of this virtue—is the powerful if not too often proleptic “virtue” that lies unmoved—is a certain anticipation tethered to Truth, rather than a dreamy vision unloosed from an imaginary pier. This kind of hope floats towards the deep a like a unmanned, mammoth, merchant vessel out of control. This kind of hope is like a ghost ship on a violent sea. There are no guarantees. There is only “maybe,” that cruelest offering.

There is another hope.

Certain anticipation is stable. It remains at the dock until the right time to move. This hope is less conspicuous than its antagonist, untethered hope. Storms come, fair winds follow, in an ever-increasing tug-of-war between the two hopes.

This is what I feel—what we feel. This dichotomy of distinctions, as comparable as opposite ends of magnet balls we played with as children, generates heat. The temperatures rage, yet they are so deeply distant from our conscious present that we rarely feel anything more than sadness.

The difference in the struggle is the Supreme Savior who stands by the pier. If need be, He will walk on water to assure us that the “line will hold.” He—Jesus of Nazareth, the fairest of Heaven, who stood before the throne of the Almighty to solemnly swear, “I will go” is, as Peter reminded us, “a living Hope.”

“Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! According to his great mercy, he has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead” (1 Peter 1:3 ESV).

Thus, Milton in Book III:

“Which of ye will be mortal to redeem

Mans mortal crime, and just th’ unjust to save, [ 215 ]

Dwels in all Heaven charitie so deare?He ask’d, but all the Heav’nly Quire stood mute,

And silence was in Heav’n: on mans behalf

Patron or Intercessor none appeerd,

Much less that durst upon his own head draw [ 220 ]

The deadly forfeiture, and ransom set.

And now without redemption all mankind

Must have bin lost, adjudg’d to Death and Hell

By doom severe, had not the Son of God,

In whom the fulness dwells of love divine, [ 225 ]

His dearest mediation thus renewd.Father, thy word is past, man shall find grace;

And shall grace not find means, that finds her way,

The speediest of thy winged messengers,

To visit all thy creatures, and to all [ 230 ]

Comes unprevented, unimplor’d, unsought,

Happie for man, so coming; he her aide

Can never seek, once dead in sins and lost;

Atonement for himself or offering meet,

Indebted and undon, hath none to bring: [ 235 ]

Behold mee then, mee for him, life for life

I offer, on mee let thine anger fall;

Account mee man; I for his sake will leave

Thy bosom, and this glorie next to thee

Freely put off, and for him lastly dye” [ 240 ]—John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book Three, lines 213–241.

Hope, the authentic hope, the “living hope” has a name. And this hope is the greater power of the two so-called. For in hope as certain anticipation, we can move from one Eriksonian epoch to another. Certain anticipation says:

“Untethered hope seems to sail under a false-flag liberty, and, so, her ‘Liberty’ is but a guise; a sinister ploy that regards movement as gain, action as victory, and sightless sailing. ‘Beware of Darkness!”

Certain anticipation is solitary but is not alone. She is courageous singularity without cowardly despair. For as surely as God set forth the seasons of the earth, and marked these changes with signs—the early-spring crocus, the summer bees-balm in clusters and daisies in clumps, the autumn leaves and naked blue skies, and winter freeze to command the underground winter wheat seeds to prepare for a glorious return. GOD has made His Son to be the center of our lives, cradling His creatures from the cruel vicissitudes of change and transforming each passageway of life into an entrance of insurmountable resilience (sometimes subdued). His life is the season of seasons, the festival of festivals, and the axis on which the soul is stabilized.

Choose Advent: the certain anticipation that Christ was born, Christ has died, and Christ will come again.

So, then, welcome Advent. Welcome, hope.

Postscript

I was greatly moved by today’s greeting from the Anglican bishop of North Carolina. I share his summary of Advent with you: to encourage, inspire, and cultivate certain anticipation.

This week we, the church universal, mark the beginning of our church year with the season of Advent. The season of Advent is a season of preparation as we prepare to celebrate the birth of Christ. Our seasonal collects and hymns have as their backdrop the prophetic witness to the people of Israel waiting in their “lonely exile” for their Messiah. They mark as well our waiting in a lonely exile as a peculiar people for the Messiah’s Second Advent. The church seasons are meant to help us navigate the landscape of our inner being. They can, at their best, give shape and rhythm to our spiritual life. They can, at their best, provide the opportunity to recognize and embrace aspects of our life, we might wish to ignore – all within the context of the faith and our community of faith.

Bishop Steve Wood, North Carolina Diocese, Anglican Church in North America