⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 7 min read

There are times, many times, when my spiritual growth is stunted or non-existent. Perhaps it is the same with you. This may be because of your lack of meditation on the things of God. Meditation, traditionally a Christian practice, has gone by the wayside in today’s church and instead has been replaced by an Eastern understanding of the term.[i] The Buddhists and Hindus seek to empty the mind to become detached from the world. Many in the West have adopted this process today. Crucial to recovering a biblical understanding of meditation in the Christian life is studying how the Puritans, the masters of spiritual disciplines, regularly communed with God. Learning how the Puritans meditated on God and His truth will deepen your relationship with God.

There are times, many times, when my spiritual growth is stunted or non-existent. Perhaps it is the same with you. This may be because of your lack of meditation on the things of God. Meditation, traditionally a Christian practice, has gone by the wayside in today’s church and instead has been replaced by an Eastern understanding of the term.[i] The Buddhists and Hindus seek to empty the mind to become detached from the world. Many in the West have adopted this process today. Crucial to recovering a biblical understanding of meditation in the Christian life is studying how the Puritans, the masters of spiritual disciplines, regularly communed with God. Learning how the Puritans meditated on God and His truth will deepen your relationship with God.

What is Puritan Meditation?

The word, meditate means to “think upon” or “reflect.” The idea of meditation comes from Psalm 1:2 which teaches that those who delight in the law of the LORD will meditate on it day and night. The Lord commanded Joshua to do the same (Josh. 1:8), and Isaac would go out into the field to think upon the Lord (Gen 24:63). To the Puritan, biblical meditation, meant thinking about God and His Word. Meditation deals not only with transformation of the mind, but also with the heart. Puritan Thomas Watson defined meditation as “a holy exercise of the mind whereby we bring the truths of God to remembrance, and do seriously ponder upon them and apply them to ourselves.”[ii] Dr. Joel Beeke, a leading Puritan scholar, says, “Meditation was a daily duty that enhanced every other duty of the Puritan’s Christian life. As oil lubricates an engine, so meditation facilitates the diligent use of means of grace, deepens the marks of grace, and strengthens one’s relationships to others.”[iii]

The Practice of Puritan Meditation

The Puritans daily practiced biblical meditation as often as two times a day. While the Puritans prescribed no set length of time for meditation, time in meditation was understood to be taken seriously, and last as long as necessary.[iv] William Bates recommended Puritans to meditate “ordinarily till thou doest find some sensible benefit conveyed to thy soul.”[v][1] This doesn’t suggest they were to meditate indefinitely, as spiritual weakness could ensue and temptation could creep in. Instead, the major component to meditation was frequency. To achieve frequent meditation and stave off laziness, many Puritans picked a set time to meditate and stuck to it, usually in the mornings. Mornings were ideal, as early meditations would “set the tone for the remainder of the day.”[2]

The Puritans were also to meditate on the Lord’s Day and at other times such as: when one has a joyful spirit, when one is troubled by sufferings, temptations, or fears, when one is near death, when a sermon or Sacrament resonates with the heart, when one is to partake of the Lord’s Supper, and when the Sabbath nears.[3]

To prepare for their meditation, the Puritans had four tasks to complete.[vi] To not perform one of them would result in meaningless meditation. The first was to clear the mind of all worldly distractions. The second was to come to God with a heart cleansed from the guilt of sin. Third, meditation was to be approached with the utmost of seriousness. Meditation was not a fleeting matter; it had enormous potential for growth in the grace of God. Fourth, the Puritan was to find a place that was quiet and free from distraction. These were sometimes called prayer closets. Francis Bremer defines them as “small rooms meant for privacy.”[vii] However, not all Puritans went to a private room, some would take solitary walks.

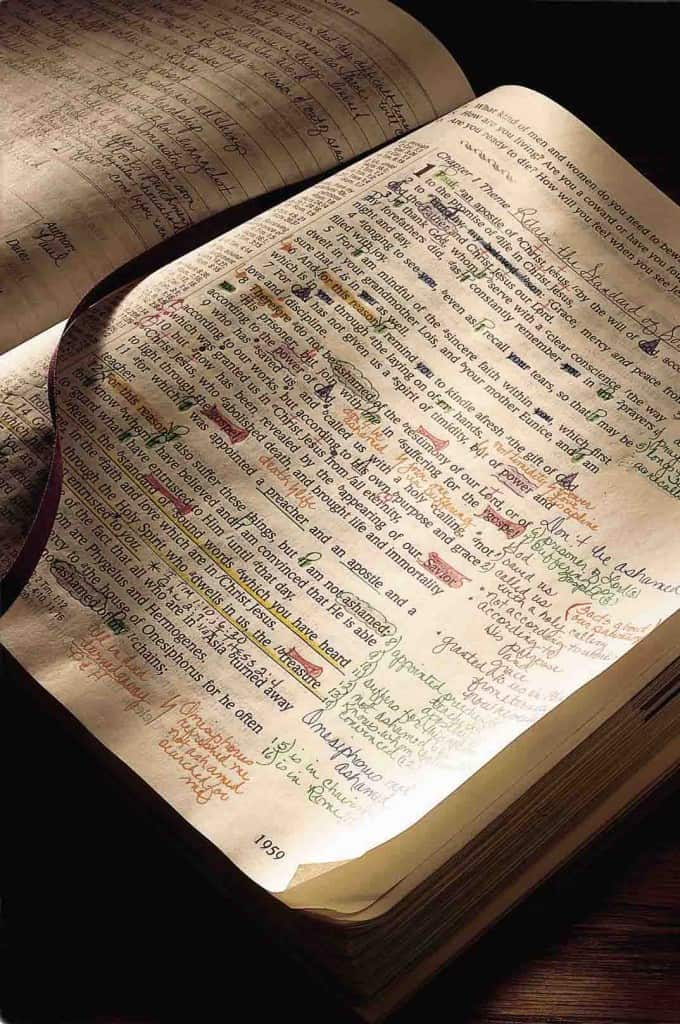

Dr. Beeke describes the process for meditation.[viii] The Puritans would begin their time of meditations with prayer, asking the Holy Spirit to help focus the mind. Next, they would read the Scriptures and pick a subject or verse on which to meditate upon. This would help them to fix their thoughts on that verse or subject. Usually the subject would be something relevant to the Puritan’s current state of affairs, such as struggles with pride, or the subject could be anything that could be found in a systematic theology book. Puritans would next examine and understand the weak or sinful spots within themselves, to bring forth those issues that they needed God to help them with. Then, they would begin to apply their time of meditation to themselves, so as to grow in Christ and flee from sin. Finally, the Puritans would write down their applications as resolutions, as Jonathan Edwards was so fond of doing. These resolutions were commitments to fight against sin, and to flee any temptations that arose. Just like meditation, the resolutions were taken very seriously, and always had a purpose in mind. The meditation would conclude with prayer, thanksgiving to God for help, and praise to the Lord, usually with singing of the Psalms.[ix]

The Practice of Puritan Meditation For Today

The aim of Puritan meditation must be recovered today so Christians can grow in Christ. Tom Schwanda says, “most Evangelical Christians recognize the importance of our union with Christ. However, it is typically limited to the forensic nature associated with justification.”[x] If meditation, and the other spiritual disciplines, were practiced regularly, Christians today would significantly benefit in their understanding of the “union with Christ to include the full doctrine of communion or spiritual marriage with Christ” and thus will enjoy the “relational intimacy that Jesus offers to all who will embrace it.”[xi] Such intimacy would enable the Christian and the Church to commune with God and sing praises of joy to Him. Meditation provides the balance between the unique walk that the Christian takes among the objective Word and the Holy Spirit. It involves the intellect and the affections. To grow in Christ, Christians must “be transformed into a welcome dependency upon the Word and Spirit through a sanctified imagination to experience the fullness of God.”[xii] Meditation focuses not on external behavior but on inward transformation by the Spirit. The focus of meditation is not on what one can get out of it, but on the question, “How can I experience transformation in all of my life?” By focusing only on the externals, we’ll receive nothing, but by desiring more of God, we’ll experience both internal transformation and outward transformation in our daily behavior. Meditation turns one’s heart away from mere benefits, worldly or spiritual, to God Himself.

It is this, the desire for God, which modern Christianity has long lost and must recover. If there is no growth, the light that shines forth in the world is dim, and the world will continue to stumble in darkness. This is why one must look to the past to answer the problems of the present to shape the future. The Puritans were masters of the spiritual disciplines, especially meditation.

The example of the Puritans has much to teach us. While we’ve only scratched the surface in this article on this subject matter, I encourage you to look at some of the authors quoted in the footnotes such as Dr. Joel Beeke’s book The Puritan Practice of Meditation. Practicing biblical meditation will help you to grow in your understanding of God, His Word, and the Son of God Jesus Christ with the result that you’ll desire more of God, hate your sin, and shine the light of Christ before a watching world.

[1] William Bates, The Whole Works of the Rev. W. Bates, Vol 3 (Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1990), 125.

[2] Beeke, 94.

[3] Thomas Manton, The Complete Works of Thomas Manton, Vol. 17 (Lightning Source Inc., 2002) 298.

[i] John Davis, Meditation and Communion with God: Contemplating Scripture in an Age of Distraction (Dowers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2012), 15.

[ii] Joel R. Beeke, “The Puritan Practice of Meditation” (Heritage Netherlands Reformed Church, 2003), 86-87.

[iii] Joel R. Beeke, “The Puritan Practice of Meditation” (Heritage Netherlands Reformed Church, 2003), 86-87.

[iv] Ibid., 95.

[v] William Bates, The Whole Works of the Rev. W. Bates, Vol 3 (Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1990), 125.

[vi] Beeke, 96.

[vii] Francis Bremer, Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America Volume 1, (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Inc., 2006), 509.

[viii] Beeke, 97-101.

[ix] Beeke, 101.

[x] Tom Schwanda,“’Hearts Sweetly Refreshed’: Puritan Spiritual Practices Then and Now”Journal of Spiritual Formation & Soul Care no 3, 1 (Spring 2010): 40.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.