⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 11 min read

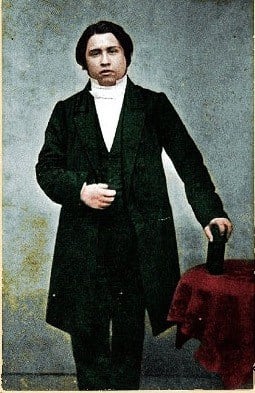

On February 17, 1860, citizens from Montgomery, Alabama, gathered in the jail yard to burn the “dangerous books”[i] of Charles Haddon Spurgeon, the most popular preacher in the Victorian world. A newspaper recorded the event:

Last Saturday, we devoted to the flames a large number of copies of Spurgeon’s Sermons…We trust that the works of the greasy cockney vociferator may receive the same treatment throughout the South. And if the Pharisaical author should ever show himself in these parts, we trust that a stout cord may speedily find its way around his eloquent throat.[ii]

Throughout the Southern states, anti-Spurgeon bonfires were lit near bookstore, courthouses, and on plantations. Anyone who sold Spurgeon’s sermons in North Carolina faced imprisonment for “circulating incendiary publications.”[iii] What had this twenty-six-year-old London preacher—the Prince of Preachers—done to solicit so much violence in America?

Spurgeon was born on June 19, 1834, only one year after the English abolitionist William Wilberforce died. Even in his youthful preaching, Spurgeon recognized the evils of slavery and social injustice. “Ah! poor negro slave,” he said, “every scar upon your back shall have a stripe of honour in heaven.”[iv] Two years before Americans burned his sermons, Spurgeon preached:

I was once complimented by a person, who told me he believed my preaching would be extremely suitable for blacks—for negroes. He did not intend it as a compliment, but I replied, “Well sir, if it is suitable for blacks I should think it would be very suitable for whites; for there is only a little difference of skin, and I do not preach to people’s skins, but to their hearts.”[v]

Spurgeon’s combat against slavery manifested in different ways throughout his ministry, but none more poignantly that in his friendship with Thomas L. Johnson—a former enslaved man from Richmond, Virginia, who was trained by Spurgeon at the Pastors’ College. In his memoir, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, Johnson described his first encounter with Spurgeon: “His first words set me at ease, but his sympathetic kindness was beyond my highest hope…The fear all vanished, and I felt I had been talking to a dear loving friend.”[vi]

Spurgeon’s sympathy for those suffering extended beyond slavery into London’s poorest neighborhoods. Without a proper sewage system, disease became a constant threat. During Spurgeon’s first year in London, ten thousand people died from a massive water-born cholera outbreak that killed many in his own congregation. At risk of his own life, Spurgeon visited the sick and dying, saying:

All day, and sometimes all night long, I went about from house to house, and saw men and women dying, and, oh, how glad they were to see my face. When many were afraid to enter their houses lest they should catch the deadly disease, we who had no fear about such things found ourselves most gladly listened to when we spoke of Christ and of things Divine.[vii]

The opening lines of Charles Dickens’s 1859 novel A Tale of Two Cities, though written about the French Revolution, also describes the London Spurgeon knew: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”[viii] In the 1840s, half a million Irish fled the potato famine and immigrated to London. By 1857, there were 8,600 registered prostitutes, or “fallen women”, living in Spurgeon’s ministerial district.[ix] The world’s largest city struggled to cope with the surging populations. Mothers, unable to feed their infants, often resorted to throwing them into the River Thames instead of letting them starve.

Orphans could be seen at every corner. Children from the ages of three and four often slaved alongside their parents in textile factories and coal mines. Employment for children could be found, but the price was high. Cleaning London’s narrow chimneys required small hands, and many “sweeps” died in their teens from respiratory illnesses and cancers.

Spurgeon walked along the southern bank of the River Thames, weeping for those he passed. But the pastor of the largest Protestant church in Christendom did more than just weep. In 1867, an Anglican widow donated £20,000 for the construction of an orphanage that could house 500 boys. Ten years later, a girls’ wing opened.[x] Engraved into the stone wall beneath the archway of the orphanage were the Hebrew words “Jehovah Jireh” (the Lord will provide). Spurgeon pointed to the wall and told his friend William Hatcher, “That is my bank. It never breaks, never suspends, never gets empty. My children have never lacked for covering, or for food and I have no fear that they ever will.”[xi]

Spurgeon’s church, the Metropolitan Tabernacle, was described by some as a beehive of activity. There were two worship services on Sunday, a prayer service on Monday, and often an additional sermon on Thursday. Children were taught how to read and write in the basement throughout the week. Spurgeon led conferences in the Tabernacle to raise support for missionaries like Hudson Taylor in China. Thousands of copies of Spurgeon’s sermons, books, and Christian literature were printed in a workshop beside the Tabernacle and distributed by Spurgeon’s wife, Susannah, as part of her ongoing Book Fund ministry.

Spurgeon had been mentoring a group of students since 1855; however, a larger theological college was needed to train the growing number of ministers. The first stone was laid for the Pastors’ College in 1873. Spurgeon selected “Et Teneo Et Teneor” as the motto “I Hold and Am Held.” The mission of the college was to train underprivileged ministers who could not afford an education. The new facility on Temple Street allowed dozens of students to be trained, and the College exists even to this day.[xii] Every Friday, Spurgeon lectured at the Pastors’ College on preaching (later collected in a bound series entitled Lectures to My Students).

By June 18, 1884, one day before Spurgeon’s fiftieth birthday, he had founded sixty-six ministries in London, including a clothing drive, book distribution ministry, a Sunday school for the blind, ministries to policemen, and nursing homes, among dozens more. Spurgeon personally shouldered the ministries’ financial needs, funneling his book earnings back into these initiatives. The pastor who, over the course of his life, had earned multi-millions of pounds died with only £2,000 to his name because he gave it all away.

Spurgeon empathized with those in his city who were suffering. In 1867, he suffered his first attack of chronic nephritis, or Bright’s disease. His failing kidneys often left him constantly fatigued. At thirty-five, Spurgeon was also diagnosed with gout, an arthritic disorder, which prevented him from even opening his hand. He once claimed, “I thought a cobra had bitten me and filled my veins with poison.”[xiii] Spurgeon’s friends sent him so much medicine that he once claimed he “would have been dead long ago if we had tried half of them.”[xiv]

Depression added to the pastor’s problems. He said, “I think it would have been less painful to have been burned alive at the stake than to have passed through those horrors and depressions of spirit.”[xv] He often wept without knowing why. Susannah often found him stretched out prostrate on the floor of his study. Each winter, Spurgeon traveled to Menton, France, to escape the dreary conditions of London.

Spurgeon’s suffering drove him to identify with London’s beleaguered working-class. “You must go through the fire,” he said, “if you would have sympathy with others who tread the glowing coals.”[xvi] Spurgeon also praised God for his pain, knowing that God was using his suffering to produce in him holiness, purity, and a deeper longing for heaven. Near the end of his life, Spurgeon declared:

I, the preacher of this hour, beg to bear my witness that the worst days I have ever had have turned out to be my best days, and when God has seemed most cruel to me, he has then been most kind. If there is anything in this world for which I would bless him more than for anything else, it is for pain and affliction. I am sure that in these things the richest, tenderest love has been manifested to me. Our Father’s wagons rumble most heavily when they are bringing us the richest freight of the bullion of his grace. Love letters from heaven are often sent in black-edged envelopes. The cloud that is black with horror is big with mercy. Fear not the storm, it brings healing in its wings, and when Jesus is with you in the vessel the tempest only hastens the ship to its desired haven.[xvii]

At 11:05 pm on January 31, 1892, Spurgeon fell into a coma from which he did not awake. His wife accompanied her husband’s body from France to England. More than 100,000 people attended his funeral. B. H. Carroll, the founder of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, observed, “If every crowned head in Europe had died that night, the event would not be so momentous as the death of this one man.”[xviii] Even newspapers in Kansas City, Missouri, where Spurgeon’s personal library would eventually reside,[xix] reported, “The death of Charles Spurgeon removes the most commanding figure in the Protestant Church.”[xx]

Spurgeon once said, “I would fling my shadow through eternal ages if I could.”[xxi] Indeed, his shadow has spilled into our age. His love for the poor, bold Christian witness, and uncompromising stance for the preaching of the gospel continues to inspire. Through his writings and sermons, younger generations are learning about what God accomplished through the life and legacy of the Prince of Preachers.

The prophecy uttered by slave-holding booksellers about Spurgeon in the American South has proven false: “We venture the prophecy that his books in [the] future will not crowd the shelves of our Southern book merchants. They will not; they should not.”[xxii] Actually, his books are becoming more widely-read today than even in his own lifetime. Who knows what spiritual fruit his ministry may one day harvest? “Who knows where my successor may be?” Spurgeon once said. “He may be in America.”[xxiii]

[i] “Burning Spurgeon’s Sermons,” The Burlington Free Press (March 30, 1860).

[ii] “Mr. Spurgeon’s Sermons Burned by American Slaveowners,” The Southern Reporter and Daily Commercial Courier (April 10, 1860).

[iii] “Rev. Mr. Spurgeon,” The Weekly Raleigh Register (February 15, 1860).

[iv] Containing Sermons Preached and Revised by the Rev. C. H. Spurgeon, Minister of the Chapel, 6 Vols. (Pasadena, TX: Pilgrim Publications, 1970–2006), Vol. 2, 103.

[v] The New Park Street Pulpit, Vol. 4, 397.

[vi] Thomas L. Johnson, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave; or, the Story of My Life in Three Continents (London: Christian Workers’ Depot, 1909), 89.

[vii] C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography. Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, by His Wife, and His Private Secretary. Vol 1 (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1899–1900, The Spurgeon Library), 371.

[viii] Charles Dickens, “A Tale of Two Cities: In Three Books. Book the First. Recalled to Life. Chapter 1. The Period,” All the Year Round, A Weekly Journal Conducted by Charles Dickens (April 30, 1859), 1.

[ix] E. M. Sigsworth and T. J. Wyke, “A Study of Victorian Prostitution and Venereal Disease,” in Suffer and

Be Still: Women in the Victorian Age, Routledge Revivals (ed. Martha Vicinus; Methuen and Co., 1972; repr., New York: Routledge, 2013), 79.

[x] The Stockwell Orphanage thrived throughout Charles’s ministry and continued to function after his death (see www.spurgeons.org).

[xi] William E. Hatcher, Along the Trail of the Friendly Years (London: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1910), 249.

[xii] The Pastors’ College, now called Spurgeon’s College, continues to this day to equip ministers for the ministry (www.spurgeons.ac.uk).

[xiii] Autobiography, Vol. 3, 134.

[xiv] Charles Spurgeon, The Sword and the Trowel; A Record of Combat with Sin & Labour for the Lord. 37 Vols (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1865–1902, The Spurgeon Library), February 1875.

[xv] The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit, Vol. 53, 137-138.

[xvi] The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit, Vol. 32, 590.

[xvii] The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit, Vol. 27, 373.

[xviii] B. H. Carroll, qtd. in Lewis Drummond, Spurgeon: Prince of Preachers 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1992), 751.

[xix] For information about The Spurgeon Library, visit www.spurgeon.org.

[xx] The Kansas City Times, February 1892.

[xxi] W. A. Fullerton, C. H. Spurgeon: A Biography (London: Williams and Norgate, 1920), 181.

[xxii] The Christian Index, repr. in “Mr. Spurgeon and the American Slaveholders,” The South Australian Advertiser (June 23, 1860).

[xxiii] Autobiography, Vol. 4, 240.

Christian T. George (Ph.D., University of St. Andrews, Scotland) serves as curator of The Spurgeon Library and assistant professor of historical theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri. He is currently editing the twelve-volume series The Lost Sermons of C. H. Spurgeon (B&H Academic, 2017). For more information and to read his weekly blogs, visit www.spurgeon.org.