⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 4 min read

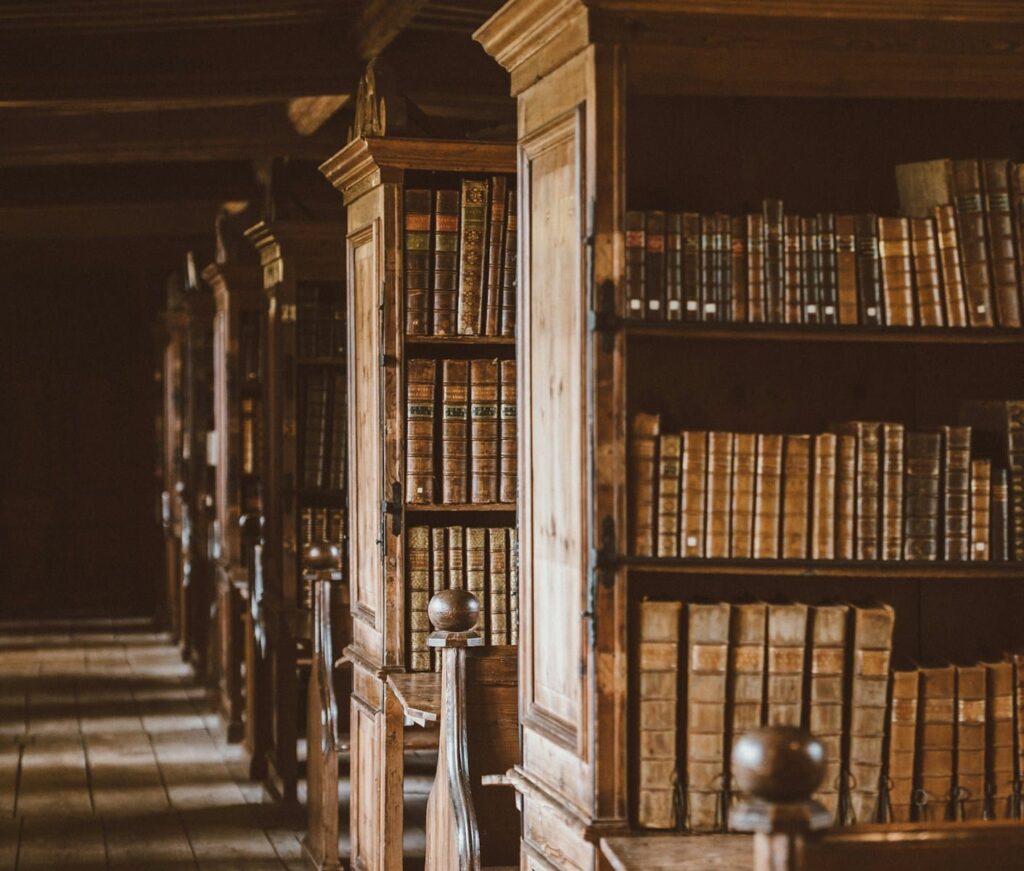

Who knows how many volumes have been written by Christians through the centuries? Spurgeon’s works alone are 63 volumes, which are equivalent to the ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Unlike Spurgeon’s works, not every Christian’s writings have been preserved, or been worth preserving.

Wesley said we ought to be people of one book, but students of many. With Scripture being our Book of books, we’d do well to learn from those Christian writings that have seemed to rise to the top and withstand the winnowing of time.

These “devotional classics” span time, denomination or tradition, and genre, for lack of a better term. They come from Ante-Nicene, Nicene, post-Nicene periods, from the Middle Ages, and from Reformation, Enlightenment, Awakening, and modern periods. They were written in Africa, Asia, Europe, and America. Their authors are early bishops, martyrs, monks, scholastics, reformers, separatists, mystics, puritans, pastors, and missionaries. They are from the Eastern and Western church, reformers who were in the Roman Catholic church, reformers who came out, and reformers who remained in. They are Anglican, Congregationalist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, and Baptist. And they write sermons, poems, confessions, prayers, autobiographies, letters, and general treatments of the Christian life.

Three Reasons to Read Classic Christian Literature

What is the value of reading these dusty treasures? I can think of three reasons.

First, the value of reading some of the best devotional works is of inestimable spiritual value. A.W. Tozer wrote:

“After the Bible the next most valuable book for the Christian is a good hymnal. Let any young Christian spend a year prayerfully meditating on the hymns of Watts and Wesley alone and he will become a fine theologian. Then let him read a balanced diet of the Puritans and the Christian mystics. The results will be more wonderful than he could have dreamed.”

Second, to be truly helpful to our generation, we should live with these past saints. Much of modern Christianity has made a host of the non-culture we call secularism, and to the degree that it has become identified with this non-culture, it has become a non-religion, simply an eclectic set of parochial pieties, idiosyncratic moralisms, prejudices and assumptions. Reading these classics is a way of hearing what generations other than our own have said. T.S. Eliot pointed out in Tradition and the Individual Talent that to enter into the stream of historical understanding is to begin to know more than the thoughts of your own generation:

“This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional. And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his contemporaneity.”

You only understand your times, and can speak to them effectively, or dare I say it, with relevance, if you have viewed your own generation from the perspective of other generations. You will only know what is distinctive (for good or ill) about your generation if you have regularly inhabited a world that transcends your particular time and place. Failing this, you are just an echo-chamber for the thoughts of our day, and if they be in error, you are a repeater-station for widely accepted error.

Someone might be understandably skeptical about the notion of orthopathy, or right loves. But let him vigorously work his way through these classics, and he will find a similarity of sentiment across the ages that seems to fit very well with the idea of orthopathy, and in many cases, makes the pieties of our age seem foreign. Don’t take my word for it. Live with Christians from other ages, and then decide whose piety is the odd one out.

Should we read writings from doctrinal traditions quite different from our own? We sit at their feet not because we want to embrace all their errors, nor because we seek to re-make them in our image (or vice-versa). A bee can find nectar in the weed as well as in the flower, said the holiness preacher Joseph H. Smith.

Finally, reading these works will mean some spiritual effort, which I heartily encourage. Again, Tozer:

“To enjoy a great religious work requires a degree of consecration to God and detachment from the world that few modern Christians have experienced. The early Christian Fathers, the mystics, the Puritans, are not hard to understand, but they inhabit the highlands where the air is crisp and rarefied and none but the God-enamored can come.”