⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 4 min read

Reality, C.S. Lewis says, is the great iconoclast. Whatever fragile ideas we may have about God, about ourselves, and about our neighbors are constantly at risk of being broken when they confront the real thing. Lewis explains that God himself is an iconoclast, and that “shattering is one of the marks of his presence,” which can be especially seen in the way that the incarnation of Jesus challenged any previously-held notions of how the Messiah would appear.

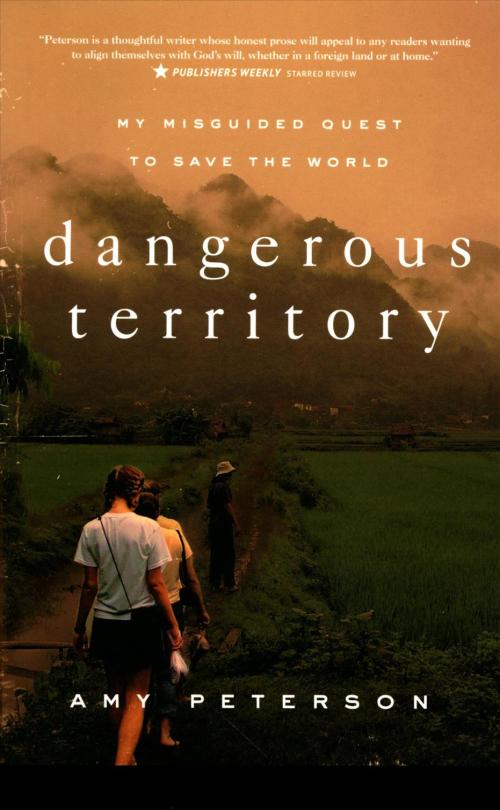

Amy Peterson’s autobiography, Dangerous Territory: My Misguided Quest to Save the World, explains how the reality of missionary work conflicted with her treasured images of what missionary work ought to be. The whole book is organized in three parts: Sent (chapters 1-15), Stripped (chapters 16-22), and Surrendered (chapters 23-30). By the time she reaches this climactic description of God as an iconoclast in chapter 25, readers will have already seen how Peterson’s ideals had been crushed by the reality of her work. Though this is first and foremost her story, what she has written also honors the heroic courage of our missionary past and offers fruitful suggestions for how we might reevaluate our missional mindset moving forward.

Peterson is honest about the complicated ways in which her own sense of adventure mingled with a sincere desire to fulfill the need for bringing the gospel to hard-to-reach places. She captures her original attitude, saying “I traveled with the confidence of the young and privileged…moving with careless confidence, trusting the world as it comes to us, believing in the essential goodness of humanity.” This, of course, is one of those ideals that will be challenged by reality, which she alludes to when she admits later on the same page “I’d like to say my confidence was founded on faith in God’s providence, but that wasn’t really it. It was simply that I was 22 and I believed I was safe and strong. I believed in adventure” (65). Her ability to recount her experiences and offer honest insight into her expectations is what makes this such a unique and helpful book on modern missions.

All throughout this honest retelling of her mixed motives, Peterson brings up important questions that apply not only to her but to all who aspire toward mission work. What do we think the world needs from us? Does the modern missionary narrative inadvertently put too much pressure on too few of us? Who do we think we are? Her story, which is frequently framed by quotes from well-known missionaries of the past, complicates the missionary narrative, offering grace to those who may have had their own “misguided quests to save the world.” Another recent book, The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving, offers an equally engaging story of a complicated missionary journey from the viewpoint of the daughter of a missionary to Haiti. Both women offer honest reflection and raise important questions about how the missionary impulse impacts the churches who send missionaries and the countries who receive them.

I felt a great deal of compassion for Amy as she allowed God to reorient her earnest and good desires. I loved watching her receive vivid and tangible forms of grace (most memorably in the form of borrowed electricity and, later, cubed watermelon) even as she experienced the pain of disappointment and uncertainty. Peterson raises interesting questions about missions and women’s roles in the church, some of which she attempts to answers and others she leaves unanswered. I don’t agree with all of her conclusions. Perhaps some of her new conclusions will have to be shattered eventually, too. Perhaps mine will, too. For now, I can testify along with Amy Peterson that God has been gracious enough to shatter what needed to be shattered but left me with a solid foundation on which to build a life of faith.