⏱️ Estimated Reading Time: 5 min read

At a farmhouse halfway between our house and our church lives a peacock. We don’t see him every time we drive by, but we always slow down to look. We’ve found him walking among the free-range chickens, hopping on the bird feeder, even perched on the handle of a tiller parked in the garden. His feathers draped over the porch railing, or the end of the truck bed are an extravagant spectacle not to be missed.

It always surprises me when my friends at church don’t know he exists. Haven’t you ever seen him? I ask. Haven’t you ever slowed down to let a car pass so you could watch him an extra minute? Once you know he exists, it’s hard not to search for him. Once you’ve seen the potential for beauty to flare in the most unexpected places, don’t you always hope it will return again?

After a lifetime of reading, one author stands out in particular for her outrageous flourishes that have kept me hunting for hints of the same beauty in every book I read. Madeline L’Engle came into my life in 6th grade through an assignment to read A Wrinkle in Time. Meeting Meg Murry was meeting a friend. Chasing her through time and space was the adventure of a lifetime. When Meg discovered love was the most powerful force in the universe, it didn’t feel like a cliche to me. It made me feel the truth of a true thing.

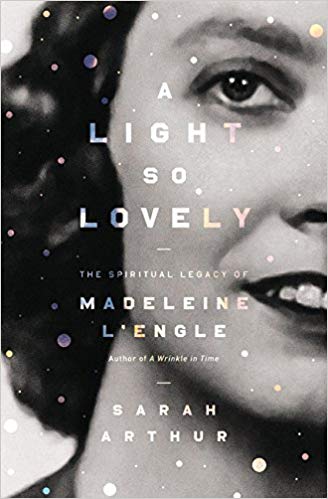

It turns out I’m not the only one who had a life-changing encounter with L’Engle’s fiction. Sarah Arthur’s new book A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeline L’Engle introduced me to a whole host of others who found L’Engle somewhere along life’s journey and were marked by this woman who, even without formal training in either science or theology, “managed to bring the two into faithful conversation” through her daring fiction (107).

This book sheds light on L’Engle’s influence as a writer who defied categorization and is organized around several paradoxes that L’Engle embodied. With chapters titled “Faith and Science,”, “Sacred and Secular,” “Religion and Art,” Arthur gathers examples from L’Engle’s writing and from those she influenced to show what a rare bird L’Engle was. As Arthur says in her introduction, when she discovered L’Engle in college she knew she “had found a Christian author who spoke my language of wonder, who somehow didn’t see things such as scientific discovery or artistic expression as threats to the gospel but rather windows by which we can see God’s light from new and exciting angles” (17).

It isn’t hard to find biographical material on L’Engle. After all, she wrote several autobiographies. A recently published biography called Becoming Madeline (written by L’Engle’s granddaughters) details her early life and reveals just how determined L’Engle was to become a writer. Instead of replaying her biography, Arthur interprets L’Engle’s legacy, both by drawing on her own understandings and through interviews with people who knew L’Engle closely and from several generations of those who admired and were influenced by her work. A Light So Lovely will introduce the uninitiated to a woman whose fiction dared to defy all categorization and will give fans a powerful understanding of the woman behind favorites like A Wrinkle in Time and Walking on Water.

Ultimately, this book becomes a celebration not only of L’Engle but of the very power of fiction (a subject of which Sarah Arthur is herself well-versed, as the author of several literary devotionals and the preliminary fiction judge for the Christianity Today Book Awards). L’Engle believes in the power of storytelling because stories reveal our “faith that the universe has meaning, that our little human lives are not irrelevant, that what we choose to say or do matters, matters cosmically” (70). L’Engle believed in the imagination–“Without it, how can anyone believe in the Incarnation?” (52)–as a means by which we can understand and celebrate truth. For Madeline L’Engle, the focus was always on writing excellent stories, not preaching a message. As she said herself, “It it’s bad art, it’s bad religion, no matter how pious the subject” (138).

Reading A Light So Lovely helped me to understand what it was that made her books so unique: she peopled them with heroes who accomplished great things through vulnerability and uncertainty (87) who learned to solve problems with their (spectacularly intelligent) family and friends (106). Jeffrey Overstreet describes her appeal when he says “She puts into the world of these very ambitious, very intellectual children these illustrations of wild scientific concepts and proves to you that there is no line between the physical world and spiritual world, nor any division between the sacred and the secular” (106). Reading A Wrinkle in Time with my public school classmates, I couldn’t believe she quoted scripture alongside bold ideas about physics and biology. I couldn’t get enough.

Arthur doesn’t flinch when it comes time to tell of L’Engle’s blindspots–the way her fiction sometimes trivialized or trampled the real lives of her immediate family or her risky theological claims–in part because L’Engle herself said she was “grateful to be loved and appreciated (but) I don’t want to be adored” (46). This spiritual biography offers a chance for life-long fans and the uninitiated alike to admire L’Engle without being tempted to idolize her. Arthur’s appealing combination of personal reflection along with interviews of both L’Engle’s loved ones and fans display L’Engle in all her peculiar glory. She was indeed a rare bird, one not usually seen around these parts, but after she’s showed you the potential for beauty in the world, it’s hard not to hope you’ll catch another glimpse.